28 May Comparative Anatomy of Legs and Feet in other Animals

By Joel Bell. Podiatrist, Masterton Foot Clinic.

I was at Te Papa the other week and came across the section where they keep skeletons of all the different animals. Being a podiatrist, I found it fascinating that all the bones from the hip down in mammals were almost identical to the people I treat. If you look at cats, dogs, and horses it looks like their knee bone is pointing backwards. That bone pointing backwards is actually the calcaneus or heel bone! All these animals are actually walking on their toes!

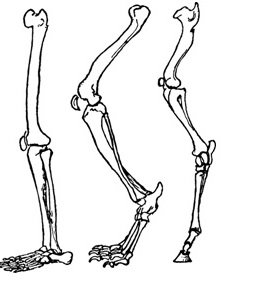

In the picture above you can see a human leg on the left, a dog in the middle, and a horse on the right. We all the share the same thigh bone structure with a knee cap facing forward and a tibia and fibula which is our shin bone.

Above is a cat’s foot. It looks like it has hammer toes! You can see the big toe/thumb doesn’t touch the ground here.

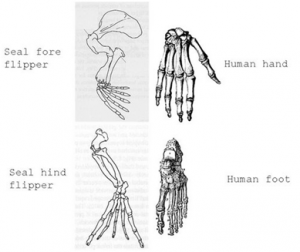

The sea mammals had similar bone structures too. The seal above has a very short femur or thigh bone and long spread out phalanges (toes) to give more propulsion in the water.

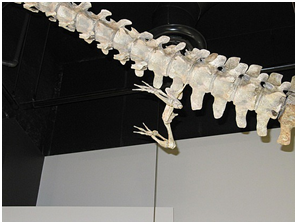

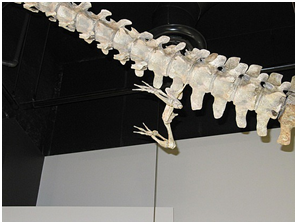

Above is a whale’s skeleton. It has tiny legs and feet that aren’t used as flippers unlike the seal.

Update (Feb 2025)

Comparing Mammalian Limbs: A Closer Look

While at first glance, the leg structures of different animals may seem vastly different, the underlying anatomy tells a different story. Many mammals share the same fundamental skeletal blueprint, but evolution has fine-tuned these structures to suit their environments and movement patterns.

Digitigrade vs. Plantigrade vs. Unguligrade Movement

Mammals walk in different ways based on which parts of their feet make contact with the ground.

Humans (Plantigrade Walkers) – you and I are plantigrade animals, meaning we walk with the entire foot, making contact with the ground—from the heel (calcaneus) to the toes (phalanges). This type of movement provides stability, balance, and weight distribution, making it well-suited for endurance walking and upright posture.

Dogs and Cats (Digitigrade Walkers) – unlike humans, dogs and cats are digitigrade, meaning they walk on their toes while keeping their heels lifted off the ground. This adaptation allows for quicker, more agile movements and efficient running, which is crucial for predators that need to sprint after prey. If you compare their skeletons, what appears to be a “backwards knee” is actually their heel raised in the air! The bones of their lower legs are elongated, providing additional spring-like function.

Horses and Other Hoofed Mammals (Unguligrade Walkers) – hoofed animals like horses, deer, and cows take this adaptation even further. They walk only on the very tips of their toes, with the bones of the foot lengthened significantly. The single visible “hoof” in horses is actually an enlarged and thickened toenail! Their entire lower limb has evolved to be lightweight, allowing them to cover long distances quickly while conserving energy.

Aquatic Mammals: Flippers, Fins, and Feet

The transition from land to water required significant modifications to limb structure in aquatic mammals. While seals, whales, and dolphins share the same basic bone structure as land mammals, their limbs have adapted to maximize movement in water.

Seals and Sea Lions – unlike whales, seals still retain external hind limbs, but their femurs (thigh bones) are significantly shortened. This reduces drag in the water while their elongated phalanges (toe bones) extend outward to form webbed flippers, providing excellent propulsion for swimming. Their front limbs remain mobile, allowing them to manoeuvre efficiently.

Whales and Dolphins – the most extreme adaptations are seen in cetaceans (whales and dolphins). Despite their streamlined appearance, their skeletons still contain remnants of hind limbs deep within their bodies—tiny vestigial bones that are no longer used. Their front limbs have elongated finger bones enclosed in a layer of connective tissue, forming strong, paddle-like flippers for steering through water.

What This Means for Podiatry

While podiatry is focused on human feet, understanding the evolution and biomechanics of different mammalian limbs gives insight into how structure relates to function. Many of the same principles apply across species—whether it’s shock absorption in the heel, the balance between stability and speed, or the role of the toe position in movement.

Even in humans, we see remnants of these evolutionary adaptations in conditions like:

- High-arched feet (pes cavus) – mimicking digitigrade animals, high-arched feet place excessive pressure on the forefoot, leading to imbalances.

- Flat feet (pes planus) – the opposite, where the entire foot contacts the ground inefficiently, reducing the natural arch support.

- Hammer toes and claw toes – a condition that, when looking at a cat’s foot structure, might remind you of their permanently flexed digits.

- Tendon and ligament conditions – just like in horses or dogs, human tendons (like the Achilles tendon) play a crucial role in movement efficiency.

By studying animal anatomy, we can better appreciate the mechanics of human feet—how they evolved for endurance walking, balance, and adaptation to different terrains. In many ways, podiatry is just as much about evolution as it is about treatment!